A Passage to India's Future

By STAN SESSER

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

February 4, 2006; Page P1

MUMBAI -- Victor Biswas, a New Yorker who arranges tours to India for museums, alumni associations and other groups of Americans, should be a happy man. He's sharing in the tourism boom to India -- his revenue last year grew 20%.

But instead of celebrating, Mr. Biswas is watching his profits vanish. His agency lets travelers lock in prices 18 months in advance, and he factors in "normal" hotel-rate increases. But five-star hotel rooms have gone up 30% or 40% in just a year. "It's killing us," he says.

Mr. Biswas's experience serves as a glimpse into the flood of change sweeping tourism in India. Travelers are coming in record numbers to the world's largest democracy, which is in the throes of an economic transition. But it isn't just the tourist industry that's being reshaped. The list of must-see places is evolving, too -- underscoring the speed of India's transformation.

In search of this new India, we picked five places that are particularly emblematic of the changes underway -- and then spent time in each of them. In Mumbai, where trendy bars, clubs and restaurants are popping up all the time, the country's exploding affluence contrasts sharply with its well-known poverty. To see how the economic shifts are impacting India's politics, we visited Kolkata, where socialist policies are getting a heavy dose of capitalism.

At the beach resorts of Goa, Indians are spending their newfound disposable income on vacations -- and quickly turning the area into one of the trendier travel destinations in Asia. Udaipur, a city rich with Indian culture and history, is grappling with strains on its infrastructure from the crush of tourism. And while the technology economy of Bangalore is well-known, the burgeoning middle class in the southern city of Hyderabad shows that this boom is spreading to other parts of the country, too.

Overall, we found that getting around India is a lot easier for novice travelers than it used to be. New airlines translate into more flight options, and more restaurants cater to upscale tourists, meaning you don't have to restrict your meals to the hotel for fear of getting sick. Some four million foreign tourists visited India last year, up 15% from the year before -- and that was on top of a rise of 25% in 2004.

But there are still plenty of hassles, from people who follow you down the street to sell you things, to the continued lateness of trains and some airlines. Indeed, thousands of airport workers went on strike across the country this week in a protest against the planned privatization of airports in Mumbai and New Delhi. (For the most part, flights took off and landed as scheduled, despite the strike.)

My swing through India showed some major infrastructure improvements. New highways are being built everywhere. A four-lane expressway from Udaipur to Jaipur, the two biggest destinations in Rajasthan, has cut travel time almost in half to five hours. And a number of airports are being modernized. The infamous, two-hour-long immigration lines at Mumbai airport are now a thing of the past.

Five new airlines have started up in the past two years, and another five are slotted to take flight this year, according to the Center for Asia Pacific Aviation. One example of how this has changed the options for travelers: Jet Airways, Indian's largest domestic carrier, quoted me a fare of $520 roundtrip from Calcutta to Hyderabad. But I was able to book flights on the Internet on two new low-cost carriers (Air Deccan and Spice Jet) for a roundtrip fare of less than $100.

All of these improvements mean it's getting harder to get into the best spots. Two years ago, I was able to book my favorite Mumbai hotel, a renovated British-era apartment house called Shelley's, just a week in advance for the peak New Year's weekend. This year, Shelley's was filled weeks ahead for the entire month of January, and so were six other Mumbai hotels I called. I ended up paying $330 a night for a room at the five-star Taj Mahal -- with no hot towel or welcome drink on arrival, no one to show me to my room, and with breakfast and Internet access not included.

Richard Johnson, director of international relations for Asia at the University of San Francisco, has seen all the problems in his 20 trips to India over the past five years. He's been a passenger in an Indian-made rental car that caught fire and then exploded on an expressway. He was caught last July in a Mumbai monsoon that was so severe that at one point his car started floating. And he's had several bouts with stomach problems. But despite all this, he says, "I'm fascinated with India."

The U.S. has now displaced Britain as the No. 1 source of visitors to India -- some 600,000 Americans traveled there last year. "We had so many people traveling to India that we had to open a second office there," says Pam Lassers, a spokeswoman for Abercrombie & Kent, the high-end international tour agency based in Oak Brook, Ill. Bookings so far this year are already up 55%, she says.

Below, the highlights from our journey.

Below, the highlights from our journey.

MUMBAI

Rajeev Samant, an Indian businessman with an engineering degree from Stanford University, recently moved to a new neighborhood. One big reason: The new bars and dance clubs there "are always buzzing until 4 a.m.," says Mr. Samant, who at 38 years old still prefers dating to marriage, to the chagrin of his tradition-minded parents. Mr. Samant, who sports a shaved head and thin gold earring, returned from the U.S. to start a winery, Sula. "Mumbai is a boom town," he says.

It is the commercial capital of India, but a capital unlike that of any other major world power. Transportation is abysmal, and the face of poverty is everywhere. But it's the best place to see the emerging young and affluent class in India: the cool restaurants, hip bars, the Bollywood stars.

The Mediterranean-fusion Indigo Restaurant, which was jammed on a recent Monday night, is now selling several $100 bottles of wine a day versus about one a month, at best, five years ago. Artists who previously needed a second job to survive are now flourishing, with prices for paintings on average doubling or tripling in the past two years alone. The number of galleries in Mumbai has quadrupled to 20, says Pravina Mecklai, who owns a gallery called Jamaat.

Some of the money in Mumbai is old wealth -- many of the country's old industrialist families still live here. It isn't uncommon to run into the son or daughter of a big textile baron who is dabbling in movie production. But new money from tech and other sectors is also fueling the club and restaurant scene.

In a country that once saw thousands of university graduates each year unable to find work, Mumbai is facing a very new problem, as the expanding service industry fueled by the new yuppie class competes for well-educated employees. "The difficulty is attracting young people to enter the hospitality business," says Raymond Bickson, managing director of Mumbai-based Indian Hotels Co. Ltd., which owns the Taj hotel chain.

GOA

As with China, Indians, armed with more disposable income, are now discovering their own country as tourists. This is helping to reshape places like Goa, the southern beach state that was once the domain of backpackers and budget travelers.

Vishal Minda, a Mumbai stock trader, and his wife Sanjanaa, both in their 20s, have visited every year for the past five years, staying at the high-end Taj Holiday Village beach resort. "We've been to Thailand and we're going to Europe in May -- but just one time," says Ms. Minda. "Goa is a place you want to keep coming back to." The state has become more accommodating to Indian tourists, she says. There are now, for example, several excellent vegetarian restaurants.

Shops offering Indian designer clothing and furnishings are springing up everywhere. The cash registers at Sang Olda, a home-furnishings store, were ringing furiously recently when the top executive of an Indian conglomerate decided to celebrate his 50th birthday in this former Portuguese colony. "His guests wiped us out," says Claudia Ajwani, co-owner with her husband. "One of the guests, an Indian who owns an IT company in California, furnished his entire California office from us," she says. "He wanted to 'Indianize' the office."

| |

The attractions of Goa are considerable. Goans are known as some of the friendliest people in India and almost everyone speaks English. The isolated beach resorts are magnificent, and a bargain compared with many other tourist destinations in India.

But Goa can be a downer at the same time. The narrow, potholed main road running along the beach towns of northern Goa is filled with horn-honking, bumper-to-bumper traffic, including beefy tattooed Europeans on motorbikes, riding past miles of schlocky souvenir shops and snack bars.

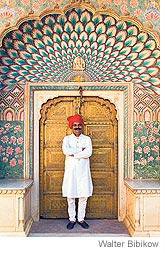

UDAIPUR

This city, a popular stop for foreigners with its elegant lakes and beautiful old palaces, has a big problem: not nearly enough places for them to stay.

While the scarcity of hotel rooms is an issue in many parts of the country, it is particularly dire here and other parts of the state of Rajasthan, which attracts more tourists each year than the Taj Mahal.

Some 1.2 million people visited Rajasthan last year -- triple the number that came just three years earlier. The shortage of rooms shows how ill-suited the infrastructure is in some ways for the level of interest in the country these days.

The very rich stay in the palaces, and the backpackers patronize the little guest houses. But that leaves out everyone in the middle. In some cases, room rates in Rajasthan have already doubled from those quoted in last year's Lonely Planet guide to India. Vinod Zutshi, Rajasthan's secretary of tourism, calculates that the state needs at least 15,000 hotel rooms (rated at least one star by the government), or triple its current stock.

The hotel shortage is creating some new opportunities for entrepreneurs. One happens to be the Maharana of Udaipur, whose family ran the state in the days of the Raj but lost all political power a half-century ago. He runs an empire of eight luxury hotels, whose rooms go for hundreds of dollars. But his latest project is the Garden Hotel, a renovated former workers' quarters whose rooms go for $70 a night.

The hotel has been an immediate success. Although it opened only last October, it's already completely full during the current peak season. "It's very difficult to get a room in Udaipur at this price," explains manager Ranjeet Singh.

The lack of hotel rooms should bring the international hotel chains scurrying to Udaipur, but it isn't happening. One explanation is that large cities like Mumbai, New Delhi and Bangalore have year-round business traffic, while Udaipur's tourism slows to a crawl in the hot summer months followed by the monsoon.

KOLKATA

It's a wonderful paradox: a Marxist government is changing this city from an economic basket base to a center for high-tech and other modern industry.

Once a proponent of radical labor laws and powerful unions, the government is now wooing companies with tax breaks and free land, in a bid to return the city to its former glory as the industrial center of India. It's a sign of just how deep-seeded the change in India is.

"Kolkata was a terrible place for so many years," says D.K. Chaudhuri, head of the computer-software company Skytech Solutions, which has offices in three Indian cities plus New York, London and Chicago, yet chose Kolkata to be its corporate headquarters. Now, "it's the most pro-active government I've ever seen. They behave like capitalists, no matter what the rhetoric."

The transformation of Kolkata -- once known mainly for Mother Teresa and abject poverty -- is one of India's great success stories. Downtown, the buildings are grimy, the air is polluted by the ancient buses and taxis, and the sidewalks serve as sleeping quarters for thousands of homeless. But a half-hour's drive away, in the spotlessly clean Salt Lake district, it's another world. Gleaming, modern buildings, reached by broad, tree-lined boulevards, house hundreds of information-technology companies. The city, formerly called Calcutta, also has one of the most vibrant cultural scenes in India, as literature, dance, modern art and music are all thriving here.

Marxist ideology still plays a role in the state of West Bengal, of which Kolkata is the capital. The government has an active land-redistribution program, for example. But "Marxism is not opposed to industrialization," says Nirupam Sen, West Bengal's minister of commerce and industries.

HYDERABAD

Ashok Hadi, an information-technology consultant at one of India's most-successful companies, knows he could make $80,000 to $100,000 a year -- more than triple his current salary -- if he moved to the U.S. But he isn't interested.

"There are many more opportunities here," says Mr. Hadi, who works mainly with American clients of the Indian software-outsourcing company Infosys Technologies.

By now, many people have heard of Bangalore, the southern Indian city that is home to some of India's most important tech companies. But the rise of Hyderabad -- often dubbed "Cyberabad" -- shows how India's information-technology prowess is spreading to other cities. That, in turn, is helping to reverse the "brain drain" of previous years.

For tourists, Hyderabad offers a pleasant alternative to Bangalore. It has vacant hotel rooms, less pollution, and fewer traffic jams. There's a picturesque Old City built when Muslims ruled the area.

Hyderabad has about 300 information-technology companies employing a total of 175,000 people -- both of those figures have tripled in the past three or four years -- says S.V. Ramachandran, regional director of the National Association of Software and Service Companies, the trade association for India's high-tech industry. "More and more Indians in the U.S. are coming back and setting up operations here," he says.

The headquarters of Indian companies in Hyderabad are as luxurious as anything in Silicon Valley. Consider Satyam Computer Services, which has revenue of $1 billion. Its wooded 120-acre campus just outside Hyderabad features not only strikingly modern buildings, an employee swimming pool and a gym, but also enclosures for deer, peacocks, rabbits and other animals. Staff doctors tend to the needs of employees, while a veterinarian takes care of the animals.

And in Hyderabad, India's second tech hub after Bangalore, a relatively small salary can go a long way. With his $24,000-a-year income, Mr. Hadi owns a 1,700-square-foot, three-bedroom apartment that he bought three years ago for $40,000. He has paid off his car, sends his son to nursery school for $400 a year and has a full-time maid.

Write to Stan Sesser at stan.sesser@awsj.com1